It’s been a very rough week in France with unbearable images circulating on social networks and some truly indecent statements in the media, following the death of a 17-year-old fatally shot by a police officer. I’ll refrain from commenting on the substance of the matter, but rather provide some factual insights into the role of social networks and social media in contributing to such an explosive outcome and fueling hatred.

The numbers are mind-boggling. On TikTok, videos tagged #emeute (riot in English) have already generated 570 million views in France. Combining different hashtags, the figure probably gets to a billion, and that’s just on this one platform alone. To put it into perspective, the final of the FIFA World Cup between France and Argentina attracted only 29.4 million viewers in France. On Snapchat, the platform is also racking up significant numbers. Even for social media experts, it’s difficult to find the right words to characterize the extent of what’s happening.

A monster fueled by the concatenation phenomenon

The non-stop flow of content is massive, live-streamed, emotional, and endlessly relayed by countless communities without people actually having time to process the information and gain clarity. To my knowledge in France, it’s the first time I’ve observed a phenomenon of such magnitude that combines real actions, agit-prop, wars of opinion, ongoing political stands & comments, all on a national scale.

In his 2016 book*, French journalist Philippe Vion-Dury pointed to the massive scaling and distortive effect that major digital platforms operate on word-of-mouth.

“By multiplying the quantity and nature of the data, the very essence of platforms’ modus operandi has changed, allowing for far greater precision in analyzing not just collective but also individual phenomena. […] from mass statistics and rough probabilities, we are moving towards a completely different regime, one that is individualized, precise, invisible, and omnipresent, capable of reshaping society.” Philippe Vion-Dury

In 2016, it took a company like Cambridge Analytica to influence public opinion. Seven years later, any activist can take advantage of social media, provided they understand a key mechanism called concatenation. What exactly is concatenation? According to Merriem Webster:

“a group of things linked together or occurring together in a way that produces a particular result or effect; the act of concatenating things or the state of being concatenated : union in a linked series”

In essence, instead of categorizing content in a traditional way (e.g., cooking, fashion, cats, etc.), TikTok creates its own categories, its own “sides.” In other words, TikTok continuously analyzes emerging sequences of actions and suggests them to users whose profiles match the initiators’. TikTok accepts a margin of error in this system and continuously adjusts the criteria and audiences to whom it serves this content, fine tuning along the way. It is the users’ boundless human creativity that ends up doing the platform’s heavy lifting by crafting logical sequences; content creators, in turn, see an opportunity and start creating custom content for these new logical chains. These logical chains often hit the mark, appealing to people’s deepest emotions or existing cognitive biases.

Centripetal vs. centrifugal

This is what’s monstrous about the shared content in recent days: everyone’s biases are reinforced through the work of both highly structured real extremists and each one of us as we educate the social networks’ algorithms so they can serve us more and more violent and exclusive content. It’s disturbing to see the number of personal stories shared in Instagram Stories or lengthy Facebook posts that, while interesting individually, end up bolstering the credibility of lies or inaccuracies that get thrown into the same sides of digital platforms. The context is often stronger than the concept.

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han summarized the issue for NOEMA:

“Truth, the provider of meaning and orientation, is also a narrative. We are very well informed, yet somehow we cannot orient ourselves. The informatization of reality leads to its atomization — separated spheres of what is thought to be true. But truth, unlike information, has a centripetal force that holds society together. Information, on the other hand, is centrifugal, with very destructive effects on social cohesion. If we want to comprehend what kind of society we are living in, we need to understand the nature of information.” Byung-Chul Han

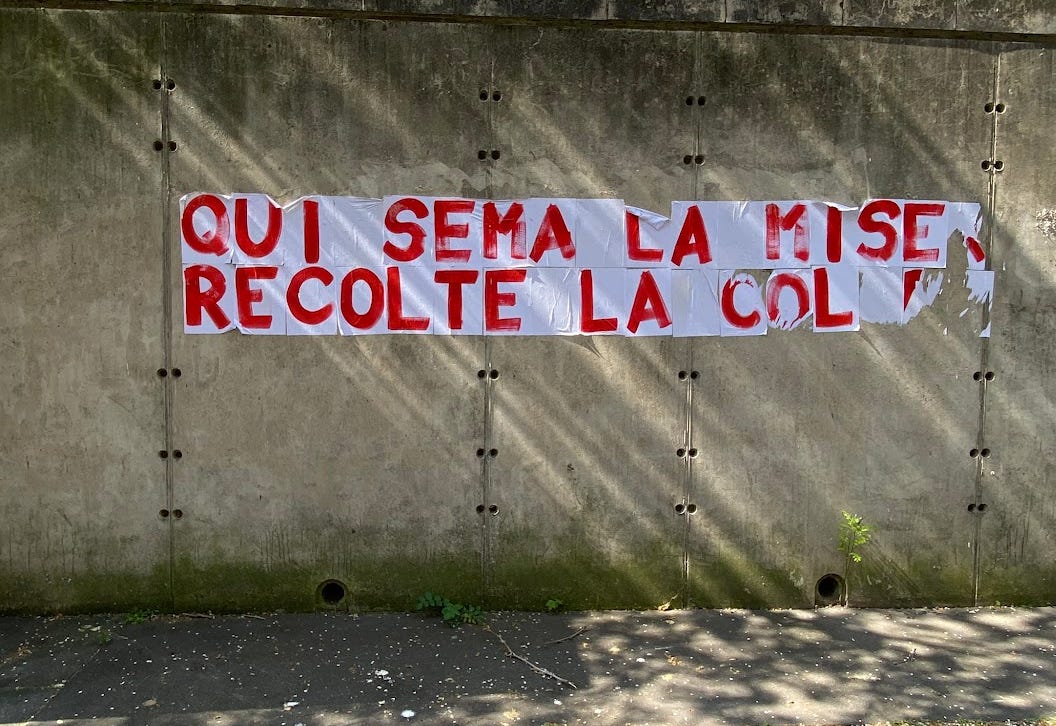

Some actors are playing a highly dangerous game. French media mogul Vincent Bolloré has understood how to push his political project: he no longer attempts to sell or gain access to our “available brain time” but rather to take up our brain time. Flooding content with consent might be a new political weapon, one that will not allow democracy to thrive in social networks.

*La Nouvelle Servitude Volontaire, Enquête sur le projet politique de la Silicon Valley